by Hamilton E. Davis

A sort of collective madness has settled over the health care reform environment in Vermont.

Within the compass of a couple of months, we are seeing a new north-of-$3 billion tab for our hospital system; the first change in leadership at the UVM Health Network in 14 years; a seismic upheaval in a Green Mountain Care Board membership that has been in place for five years, accompanied by a critical shift in its staff; new leadership in the Vermont hospital trade group; and a new management regime at OneCare Vermont, the state’s lone Accountable Care Organization.

Not to mention that the Vermont Legislature, which writes the laws for our tiny, cold, northern village, will open its January session with nine new chair people and a new boss for the Senate—a shift of historic magnitude. None of these developments, however, quite match up to what is now happening in the administration of Gov. Phil Scott, who took office in 2017 and is seeking a third two-year term, which he will surely get.

A Vermont Journal has to start somewhere in trying to illuminate the above landscape and the events in the Rip van Winkle department of the Scott administration is as good a place as any. I will post analyses of all these aspects of reform as possible.

After basically ignoring the reform project for the first five years of his tenure, Gov. Phil Scott woke up on June 1 and launched a frontal assault on the Green Mountain Care Board, a majority of whose members he appointed. The Scott sortie was clearly an overreach, given that all the real power over the Vermont hospital system remains with the Green Mountain Care Board.

That does not mean, however, that there is no bill of particulars against the performance of the Green Mountain Care Board. The Board has been a sort of slow-moving train wreck, doing nothing about the huge problem of wasted and questionable quality care in the Vermont community hospital system while keeping statewide costs under control by steadily draining money out of the UVM Health Network, particularly the UVM Medical Center in Burlington, to the point that the whole academic medical center is at serious financial risk. The members did so in the face of compelling evidence that the Network hospitals deliver the highest quality care in the state, at the lowest per capita cost—by huge margins.

That 800-pound chicken, in turn, has come home to roost in the form of the Medical Center’s Fiscal Year 2023 budget, filed last Friday, which calls for total expenditures of $1.659 billion, a full 10 percent or $150 million over the current year’s $1.509 billion total. The UVMMC request is more than double the GMCB cap, although that cap is pretty squirrelly.

Moreover, taking in that much revenue can’t be accomplished without increasing UVMMC’s charges to payers like Vermont Blue Cross and MVP by 19.9 percent, or $36 million, a hit that will be reflected in Blue Cross premiums and will draw howls of protest from the carriers, advocates for the poor, and such marginal players as the Health Care Advocate and the Vermont Auditor. The Board has never granted an increase of that magnitude.

The backdrop for this back and forth is an unsettled structural situation, marked by the need for the Scott administration to find a new chair-person for the Green Mountain Care Board to replace the retiring Kevin Mullin; the UVM Health Network Board is now interviewing potential replacements for Dr. John Brumsted, who directs or strongly influences 60 percent of the care in the state, and is retiring after 14 years; and VAHHS, the hospital association, is seeking to replace Jeff Tieman, the president of the trade group, who has been a significant player in the reform space. Mike Del Trecco is the interim CEO of VAHHS.

It will be difficult for even my tiny corps of brilliant readers to get their arms around this tangle, so I will break it into chunks over the next several weeks. A good place to start will be the UVMMC budget and the GMCB’s management of it over the last five years. Because getting that wrong could deprive Vermont of its most significant health care asset, and the Vermont economy’s single most important prop.

The UVM Network’s Role in Vermont, and GMCB’s Management Performance

Since 2015, UVM’s critics have charged it is too big, too dominant over smaller players, and too grasping of money and control. The evidence flatly contradicts those claims.

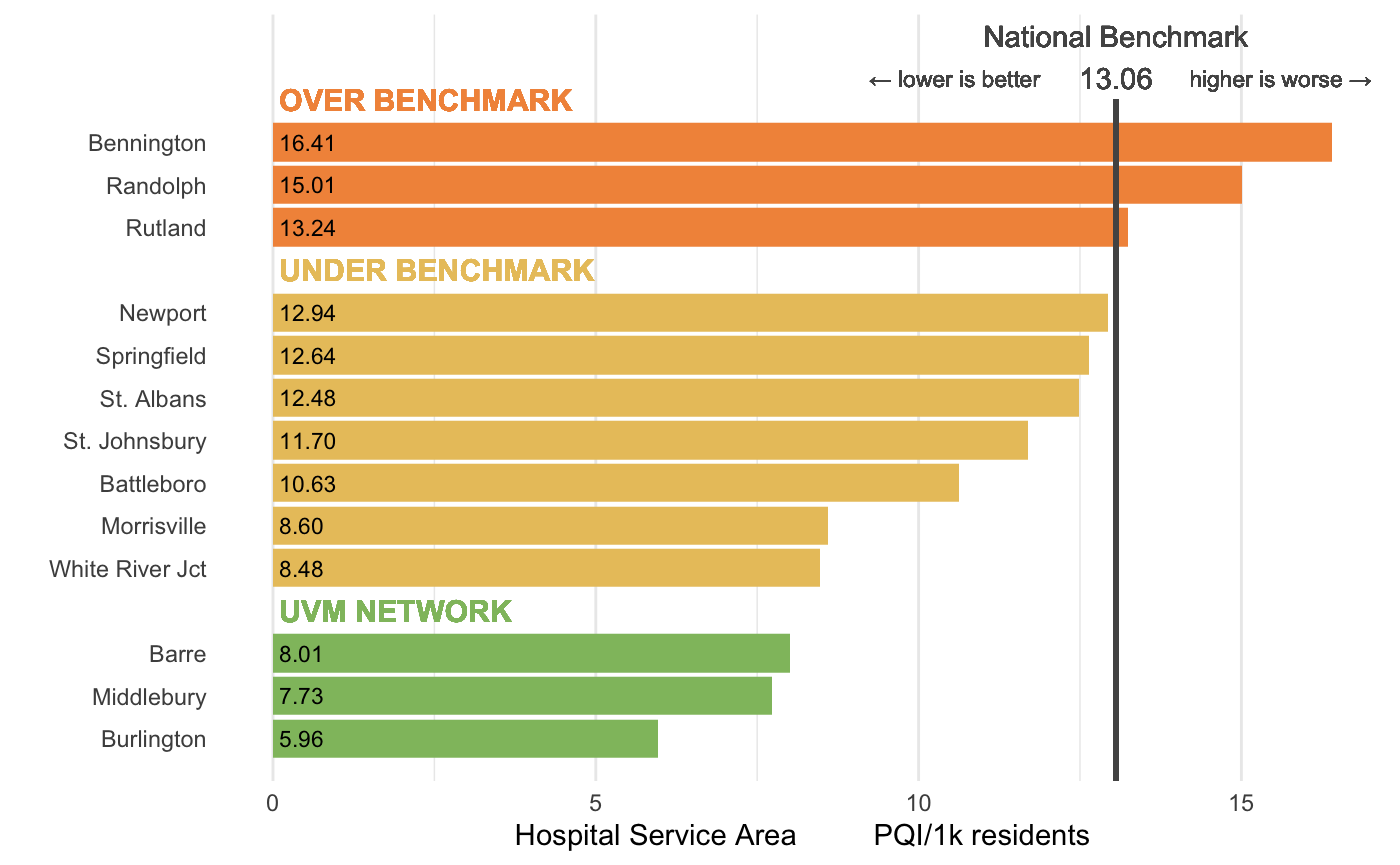

First, the single most important national data source for health care reformers is the Dartmouth Atlas for Health Care, the DH Atlas, for short. This publication shows the Medicare spending per capita in hospital service areas in the United States. The data are adjusted for age, race, and gender to enable apples-to-apples comparisons. Within Vermont, the results look like the graph below:

The findings shown above demonstrate that the financial performance on a cost per capita basis for the UVM Health Network are not just the best in the state, but best by a huge amount. Moreover, a striking anomaly in the data is the finding that other two Network hospitals in Vermont, Central Vermont Medical Center in Berlin with just over 100 beds, and Porter Medical Center in Middlebury with just 25 beds are as economically efficient as the academic medical center. (I’ll discuss the phenomenon in another post)

Second, in draining so much money from UVMMC, the Board has put the hospital and the people of Vermont at significant risk for having to pay higher interest rates to borrow money. The cost of borrowing is set by three national rating agencies—Standard & Poor, Fitch and Moody. Nearly all major hospitals maintain an A rating on their bonds. The Medical Center lost its “A” several years ago, and the Brumsted administration had to struggle for 10 years to get it back.

The graph below illustrates how perilous UVMMC’s position is now. A critical metric to assess financial health for a business is Days Cash on Hand, the amount of money needed to keep the doors open with no revenue coming in.

The rating agencies have held off punishing hospitals during the Covid pandemic from 2020 until now, but by next winter that piper will have to be paid. And the price is likely to require the Board to endorse a really big increase, one that will have to not only account for the current raging inflation, but for the depredations of the last five years. The evidence for the drain is shown graphically by the UVMMC ratings over the last seven years.

Third, a persistent question in the health care reform space is whether cutting the waste out of the community hospital network will lead those hospitals to deprive patients of necessary care to save money. The following graph demonstrates the fallacy inside that speculation. A national consultancy addressed that question for the GMCB in a report delivered last fall. The metric the consultant used is called Prevention Quality Indicator, PQI. If an episode of care is judged not necessary, then that block of care is by definition of low quality. The results show the clear superiority of UVMMC and network quality over the rest of the system. The take-home message: high quality and low cost go together, a message GMCB has ignored over that period.

Governor Scott responded strongly to this situation shortly after the legislative session ended when S285 came to his desk for signature. The bill appropriated $4 million to the Green Mountain Care Board to study the advisability of shifting the focus of reform from specific action by the GMCB to the establishment of Global Budgets for hospitals—a different kind of regulatory mechanism. The measure also gave the Director of Health Care reform in AHS $900,000 to work on reform.

In a letter to legislators dated June 1, Scott said he would sign the bill, but that he was hesitant to do so. “Stabilizing our health care system has become increasingly urgent,” Scott wrote. The system, he continued, is increasingly fragile coming out of Covid and it now “confronts the impacts of deferred care, an aging population, a workforce crisis and the historically high inflation that increases the costs supplies, energy, and staff. With all these factors, the system is at risk of significant disruption and instability.

“While I do not believe the Green Mountain Care Board should be in a policy development role, given the fiscal crisis our health care system faces—and the affordability crisis it will present to Vermonters—time is not on our side,” the Governor wrote.

In order to ensure that the total $5 million is “deployed quickly and in very close coordination with my administration, the Legislature and stakeholders,” Scott said he had “directed the Agency of Human Services and the Department of Financial Regulation to provide active oversight” (emphasis added) of the GMCB’s use of the resources in S285. In agenda would be to deal first with stabilization, then regulation, then the form of the All-Payer Model, and finally long-term consideration of how a fully sustainable system would work. These are highly abstract terms, each of which could be elaborated over thousands of words; but there was no mistaking the tone of his comments.

In his letter, Scott said his two agencies “would hold the GMCB accountable” for “thoughtful” decisions on hospital budgets and insurance rates. And the mission of his executive-level committee would be to “move forward with the All-Payer Model and value-based payment reform.”

So: “Active oversight, hold the GMCB accountable, move forward with reform.” There is no question that Scott’s posture here is very aggressive, especially when compared to his performance since he took office in 2017. It certainly qualifies as “leadership,” which reform advocates have pressed Scott on for several years.

If there was any doubt that Scott was denigrating the ability of the Green Mountain Care Board to do its job, they certainly faded last week when a report spread though the reform space that the administration would hire the Wakely group, a national health care consultancy, to evaluate the FY 2023 Vermont hospital budgets, which is the GMCB’s central responsibility.

An obvious problem, however, is that the executive branch of government has no authority whatsoever to interfere with GMCB decisions on hospital spending, the amount hospitals can increase their charges to insurance companies, the amount insurance carriers can increase their charges to payers, or Certificate of Need (CON) permission for hospitals to build new facilities, or install new service lines.

The only relief for an aggrieved payer or provider would have to come from the Vermont Supreme Court, and the plaintiff in such a proceeding would have to persuade the court that the GMCB decision was arbitrary and capricious.

Given these realities, it is impossible at this point to even speculate about the ultimate impact of the Scott initiative. The hospital budgets for the Fiscal Year 2023 arrived at the Green Mountain Care Board on July 1. The Board staff will analyze the budgets in July, and the Board itself will hold hearings on them in August. Their decisions on the budgets will be made by mid-September and the decisions announced formally by Oct. 1, the start of the new fiscal year. State law requires that hospitals comply with those Board decisions. Neither AHS, nor DFR, nor the Legislature will have any authority to change those numbers. Which does not mean that the activities of the Scott committee might not have an effect, only that the effect will be mostly political, although the Scotties might be able to capture some more federal money.

The Green Mountain Care Board, meanwhile, has said nothing publicly about the assault by the Scotties. Kevin Mullin, the chair of the Board, said that the members had been warned by their lawyers not to comment on budget issues while they are before the Board, but the private reaction has been frosty: you cannot have a conversation with a Board member without being reminded that the Scott administration has no authority to direct the Board, a message delivered with quiet satisfaction.

The above post is just the ante in the summer’s poker game. A Vermont Journal will look next at the Green Mountain Care Board’s positions and activities as far as they can be determined from material available before the formal budget process. A major piece of that will be a description of the large volume of independent analyses on reform that came into the Board in the last half of 2021.

That post in turn will call for a much deeper dive into the whole Scott oversight committee, and especially what’s going on with Jenny Samuelson, the new Secretary of Human Services and the field commander of the Scot forces in that unique project. Stay tuned.