by Hamilton E. Davis

A week or so ago, the University of Vermont Health Network announced that it would become the sole owner of OneCare Vermont, the state’s only Accountable Care Organization. From its inception in 2012, OCV has been owned jointly by the University of Vermont Health Network and the Dartmouth-Hitchcock health system in nearby New Hampshire. VTDigger, Vermont’s only state-wide news organ, summed it up this way:

The move is the latest in the UVM Health Network’s consolidation of power in Vermont’s health care sector and is sure to draw criticism from those who believe the sprawling non-profit has too much control over health care spending and delivery in the state.

That single paragraph captures both the toxic political environment and the bone deep ignorance that lies like a miasma over the Vermont health care reform project. And if you want to see just how far into the irresponsibility weeds it’s possible to go, you can read the commentary by Bill Schubart on VTDigger, about which more below. In fact the whole reactionary blather about the ownership shift is entirely wrong, in its supposed facts and its implications.

The UVM Health Network has no “control” whatsoever over a dime of medical spending, or the movement of a single pill or scalpel, in the 11 of 14 hospitals that lie outside UVM’s three network hospitals. And it has much less control than one would suppose even over the activities of the network hospitals in Middlebury and Berlin.

Moreover, the UVM network has no ability to exert such control through OneCare Vermont, which is controlled not by its “owner”, but by the OneCare Board of Managers in a process governed by state law. There are 21 such Managers and going forward UVM will have four representatives in a system that requires a supermajority of 14 votes on any important decision. UVM, in short, hasn’t enough power or control to determine the location of a paper clip in any of the 11 hospitals outside its own borders.

This is a devilishly difficult subject to write about because it is so complex and because so much of the public discussion about it has been marked by misinformation, sheer ignorance and outright lying. All that is compounded by the reality that at the end of the day, nothing has actually changed. So why bother? My personal reason is that public discourse in the U.S. has become badly debased, and it seems a shame to let that happen here. I hope my tiny corps will appreciate my giving it a try. In any event, herewith:

The difficulty starts with the fact that there are actually three underlying questions. The first is why did the shift in ownership take place? The second is, what difference does the shift make, and will the hospital system operate differently? The third is whether the shift represents reprehensible behavior on the part of the University of Vermont Health Network—is it a power grab, a conflict of interest, and will it damage the state’s health care delivery system?

UVM Network v. Dartmouth-Hitchcock

This is the easiest place to start. In 2012, UVM and DH agreed to jointly create an Accountable Care Organization (ACO), a contraption designed as part of the federal Obamacare legislation to permit individual hospital and doctor groups to join in offering to provide payers (Medicaid, Medicare, insurance companies) with a full range of acute medical care to large blocks of patients for a single price per capita. Hence the term, “capitation.” They called it OneCare Vermont. The point was to eliminate the huge incentive in the ubiquitous “fee-for-service” reimbursement structure to overuse of medical care, at devasting costs both financially and in quality terms.

UVM and DH invited the other 13 Vermont hospitals to become part of OneCare;12 of them did. And OneCare began the 10-year trek toward a reconfigured system. This fall the UVM Network and DH announced the change in ownership, and touched off an intense discussion in the policy space—did Dartmouth jump, or was it pushed? And how would the new configuration behave differently?

The answer is that Dartmouth jumped, but its reasons were essentially prosaic and practical. And the effect of the change going forward would be nothing all, except to give the anti-UVM and anti-reform claque a golden opportunity flog their nemesis.

When Dr. John Brumsted, the CEO of the UVM Network, and Steve LeBlanc, DH’s top strategy official, discussed the ownership change with the press they talked a lot about how it increased efficiency, etc. etc. LeBlanc was positively voluble about how committed Dartmouth is to its Vermont patients, and how supportive it is of everything that OneCare is doing. And of course, DH would maintain a single seat on the OneCare Board.

A Vermont Journal has no doubts about the sincerity of all that, but I would add a few caveats. For at least two years, DH has been skeptical about its tie to OneCare and the level of effort it takes to maintain it. Dartmouth’s primary focus has been on its customer base in southeastern New Hampshire, not to mention the prospect that Massachusetts General Hospital might poke its way north, in the same way it has begun to colonize Rhode Island. Mass General is a giant, and in 2019 it linked up with another giant, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston, and the combined unit is a behemoth that could begin to erode Dartmouth’s appeal in southeastern New Hampshire.

None of which is to say that Dartmouth doesn’t need every single Vermont patient it can attract, especially for big-ticket tertiary care. It does, because, 40 percent of DH traffic comes from Vermont, so without Vermont traffic Dartmouth is out of business. Hence Steve LeBlanc’s enthusiasm. But DH gets no real benefit from OneCare, and it definitely has no appetite for getting tangled in the Green Mountain Care Board’s regulatory net.

And, more important than anything else, Dartmouth has nowhere near the commitment to reform that Brumsted and UVM have demonstrated. Evidence? Over the past five years, 13 of Vermont’s 14 hospitals have taken full risk, fixed price contracts with Vermont Medicaid. If those hospitals delivered more care than they estimated, they had to eat the extra cost. Dartmouth’s participation in that period? Zero, not a cent.

So, that is the Dartmouth-Hitchcock situation. It is still a member of OneCare Vermont, but not an owner. And the actual effect of the shift in ownership is—nothing at all.

Ownership versus Control

The issue lying at the center of the ownership brouhaha is the distinction between ownership and control, or management. It certainly befuddled the VTDigger reporter. For much of the general public ownership means control. If you own a lawnmower, you can tell the lawnmower to just sit there in the garage, or you can make it mow the lawn. If you’re the Mom or the Dad, it’s entirely up to you whether the kids get to drive the family car. You own it, after all.

The situation is entirely different with a business, not all businesses, but a great many of them. If are the sole owner of a widget company, you can shift to manufacturing socks entirely at your own initiative. Good luck, knock yourself out.

But if you are the owner of a company with stockholders, the situation is entirely different. Consider Ford Motor Company. Ford has a gazillion stockholders—they are the owners of the company. But the stockholders, qua stockholders, have no voice at all in the control of or management of the company.

Let’s say you own $5 million dollars worth of Ford stock, and you believe that the company should shift to manufacturing cars that run on ice cream. That means nothing at all; management in Detroit wouldn’t even let you in the door. For shareholder companies are controlled by their boards of directors. If you want to move to ice cream as a motor fuel, you have to get control of the Board. Can that be done? Yes, but rarely, and certainly not easily. Of course, if support for ice cream gained sufficient momentum to move the Board, then the guys in their F-150 pickups would be driving up to the pumps to choose between strawberry, chocolate and pistachio.

At a miniature scale, OneCare duplicates that structure. OneCare is a for-profit limited liability company organized in 2012 under Vermont law. It carries the for-profit designation not because it makes a profit—it doesn’t; but because the founders confronted a kink in the interface between state and federal law. Vermont law says that non-profit companies must limit the participants in the endeavor to 50 of the total Board members. Under federal law, however, an ACO must enlist 75 percent of the participants on its Board. Hence the kink: OneCare is for profit in Vermont and is considered by the IRS to be non-profit. A conflict, obviously, but since OCV doesn’t make profits, no harm—no foul. (more about this below)

In any case, OneCare works like this:

A purchaser of medical services like Vermont Medicaid wishes to buy comprehensive care for a block of patients for a single per capita price. Comprehensive means care delivered up the intensity ladder, from primary care in a doctor’s office to moderately complex care in community hospitals to very intensive care available only in tertiary centers like the UVM Medical Center or Dartmouth-Hitchcock.

A Medicaid recipient in, say, Swanton might need to see his or her primary care doctor locally, and the patient might need more complex care at the local hospital, Northwestern Medical Center in St. Albans; if that level care doesn’t solve the problem, the patient could go to a tertiary center, like UVMMC or DH. The central idea in reform is that the route to cost containment lies in getting a single price for the care delivered in the movement of patients through the system.

The clearest example of its operation is the 2017 contract between the Vermont Medicaid agency and four hospitals in northwest Vermont—in St. Albans, Berlin, Middlebury and Burlington—to deliver all necessary acute care to 31,000 Medicaid recipients in those hospital service areas for $93 million.

OneCare Vermont, the ACO, functioned as a device to get the money into one bucket, and then distributed to the providers depending on how much care each would have to provide. That number for each hospital is determined by taking the number of lives expected to come in the door, and, given the fact that the intensity of care differs from hospital to hospital, combining the lives with the claims data for that hospital in the past.

The underlying basis for the angst over UVM and OneCare is the implicit or even explicit claim that by virtue of its ownership of OneCare that the UVM Health Network will be able steer more of the total money in a given contract to itself than is fair. And if that is the case, then the other players would get less than their fair share, since the size of the contract is fixed.

The reason for belaboring this history is to dispose of the proposition that ownership of OneCare indicts the UVM network for “conflict of interest” and putting their finger on the scale when the money from a OneCare contract is distributed among the state’s hospitals. Let’s consider that proposition:

The Operation of the OneCare Board.

Okay, okay. UVM can’t run the state’s hospitals just because they own OneCare. But they are really big, so why can’t they just capture the OCV Board? I mean, they are way more powerful than the other players in the system, and everyone says they’re really greedy and bullying, and, of course, the fact that they own the system means that UVM has a “conflict of interest” which allows them to get more than their fair share of the money flowing into the system. If you are condemned to live in the health care reform space, you will hear stuff like that every day.

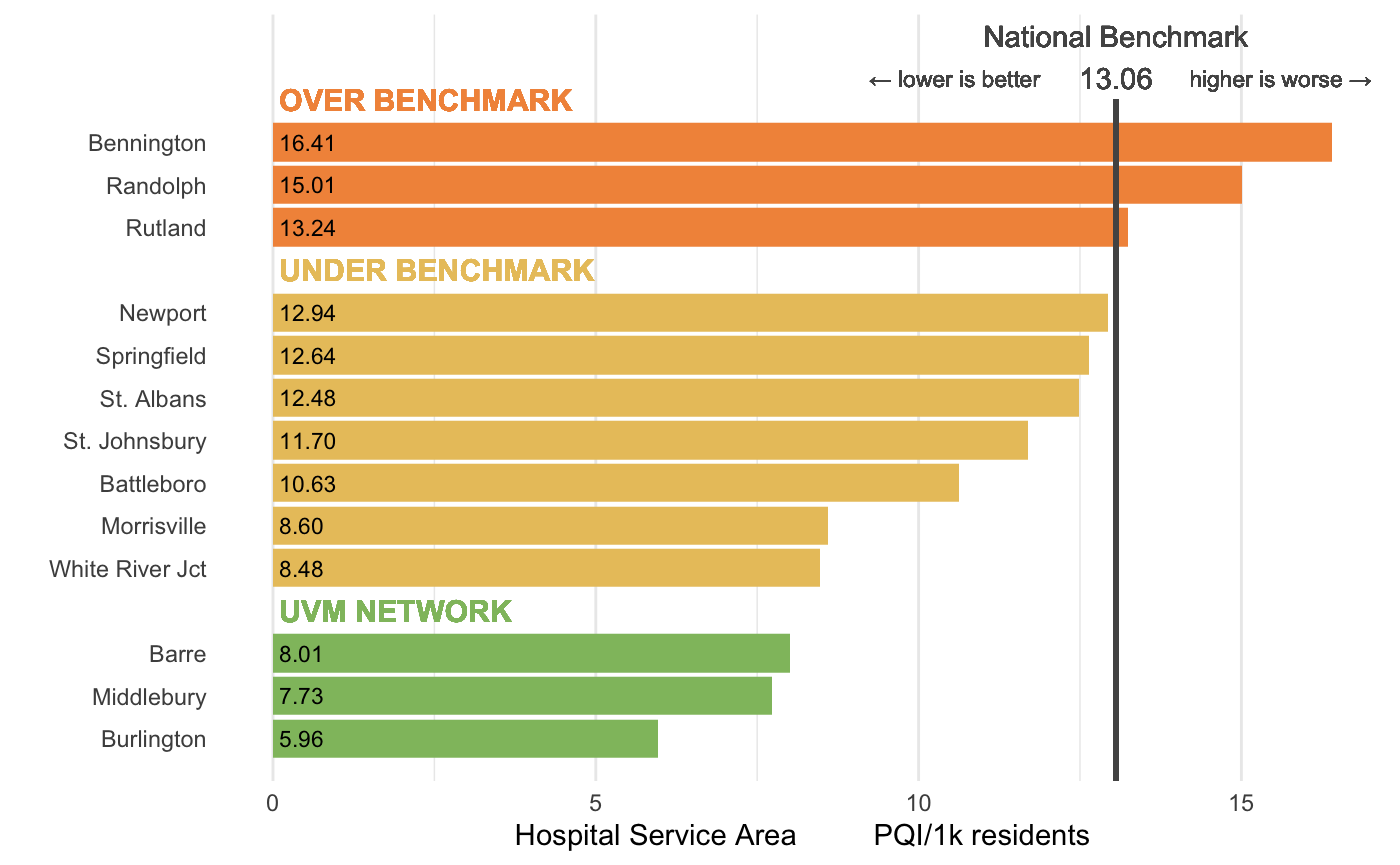

The reason why the UVM Network can’t do any of that is the existence of the Operating Agreement between the Board of Managers of OneCare itself. And it is that Board that actually determines everything that OCV does. Not only does UVM not control the Board, they have far less influence on it than is justified by their size. The UVM Medical Center in Burlington delivers about half of all the acute care in the state; its budget get runs to about $1.4 billion per year. Add in the care delivered in the network hospitals in Berlin and Middlebury and the percentage of the total runs close to 60 percent.

The Board consists of 21 members, only four of whom have anything to do with UVM. The remaining 18 members represent seven other hospitals, along with primary care practices, and other players like the Vermont Food Bank, the Vermont Federal Credit Unions and the Hospice Director at Bayada Home Health, which runs facilities in Chittenden County. Moreover, all of the important board decisions get made by a ‘supermajority” of 14 votes. UVM’s ability to control or manipulate this structure to its own advantage simply doesn’t exist, and never did.

The UVMers are outnumbered on the Board by the CEOs of Gifford Hospital in Randolph, Southwest Medical Center in Bennington, Brattleboro Memorial Hospital, Rutland Regional Medical Center, Mt. Ascutney in Windsor and a representative of Dartmouth-Hitchcock in nearby New Hampshire—six to four.

These 21 players function under the terms of the operating agreement. (Key elements of that document are listed below).

In sum, to believe the Yahoo case on that matter, you would have to believe that veteran CEOs like Steve Gordon at Brattleboro, Claudio Fort at Rutland, Tom Dee at Bennington, Dan Bennett at Gifford, Joe Perras at Mt. Ascutney in Windsor, and Michael Costa at Northern Counties Health Care are too dumb to realize their pockets were being picked. People who believe that are the truly gullible ones.

The Truly Bad Performers

Which doesn’t mean there is any shortage of players determined to make it. By far the most egregiously false and irresponsible claims on the anti-UVM case came from Bill Schubart, a former business-man who publishes commentary on VTDigger. After a series of bleak ruminations on the problems of health care in the U.S.—lack of available staffing, obesity, lack of vision and leadership “and the overwhelming inertia baked into a system that has evolved to protect the interests and privilege of all who profit from it, rather than delivering on its mission of population health and care,”-- Schubart pivots to Vermont.

The public is focused on long wait times at UVM Medical Center, Schubart wrote, “but the problems affecting Vermont’s only tertiary-care hospital run much deeper. They include lack of a clear vision, poor governance, embedded conflicts of interest, and an acquisition strategy that consolidates power, creating an unchecked monopoly with no countervailing regulatory force.”

Schubart follows that claim with a miscellany of criticisms of OneCare Vermont, the Green Mountain Care Board, and the Scott Administration…It all adds up to a lengthy indictment of the whole health care delivery system. Given the amount of misinformation that pervades the reform atmosphere, it is tempting to write Schubart’s screed as just more noise. I think, however, that at least some of my tiny corps might be interested in a full assessment of his broadside. The reason is that the public at large has no reliable source of information on this critical policy arena, as we have seen from the continuing blundering coverage by VTDigger. So, herewith:

On UVM’s posture and performance. The description of that is entirely false in general and in most of its specifics. The Vermont health care reform project leads the whole United States in the effort to shift from fee-for-service reimbursement to block financing or capitation. The original reform vision was articulated by former Governor Peter Shumlin, and in its first iteration it was designed and put into execution under the direction of the industrial-strength policy experts Anya Rader Wallack and Steve Kimbell.

But the Shumlin administration couldn’t have even started without the full support and cooperation of John Brumsted, the CEO of the UVM Medical Center in Burlington and the rest of the UVM network players in Middlebury and Berlin. There are roughly 850 ACOs in the United States, and the only one fully committed to what the federal government defines as Phase Four, full capitation, is OneCare Vermont and the only reason that is true is the commitment by Brumsted. That is why from the earliest days of reform, federal Medicare officials have put OCV in the forefront of national reform; it is why the University of Chicago’s research groups report to CMS that the Vermont program is ‘very promising’, and the testimony of national small hospital expert Eric Shell, that UVM leads the country on reform.

Shubart makes the point that the total amount of Vermont medical spending is just two percent of the total, which is true; but that is not the fault of either UVM or OneCare. The barrier to much greater participation is the refusal of either federal Medicare officials or private insurance firms like Vermont Blue Cross to permit capitated payments for their purchases of care. Even given that environment, Vermont’s Medicaid Agency now has $147 million in full capitation, while the rest of the country has---nothing.

They can go to Dartmouth for advanced care, or minor care for that matter. They can get a knee, hip or shoulder replacement at Copley, or Dartmouth, or Rutland, or Boston. And many do. A few years ago, the CEO of Copley, a 25-bed hospital in Morrisville, told the Green Mountain Care Board that without its high-end orthopedics, Copley couldn’t exist.

Moreover, anyone who thinks that the doctors in non-network hospitals in Vermont like Rutland, and Brattleboro or St. Albans operate in thrall to whatever the Medical Center thinks about medicine is just plan ignorant. Doctors at the UVM Medical Center may think that the St. Albans hospital is too small to do very complex operations like spinal fusion, but that fact has precisely zero to do with what the St. Albans doctors actually do.

Shubart claims that “UVM Health Network now has virtual control over how the money from Medicare, Medicaid and commercial insurance is spent.” That is false. See the analysis above. The 11 hospitals outside the UVM network spend their money with no reference whatever to what either UVM network, or for that matter, OneCare Vermont, thinks about it.

A major contention in the Schubart case is that Brumsted and the Medical Center are on an acquisition binge, getting control of hospitals like Porter in Middlebury and Central Vermont Medical Center in Berlin, not to mention the three hospitals in northeastern New York—all in the service of amassing more power. There is no historical evidence to support that. The affiliations with Porter and Central Vermont were rescue missions. Both the smaller Vermont hospitals asked to be taken under the UVM wing because they were going broke. If you think taking on a crashing small hospital is a power move aimed at building more revenue, you might consider why Dartmouth-Hitchcock, begged to do the same thing for Springfield Hospital, fled screaming and left Springfield to bankruptcy court. The same thing was true in New York. The New York State Health Department, which hemorrhaged money into the North Country is still grateful to Brumsted for getting their poorest region on a sustainable health care track.

In an effort to establish a clear conflict of interest, Schubart makes a connection between the fact that Al Gobeille, who spent a term as chair of the Green Mountain Care Board in the ‘aughts and then a couple of years as Secretary of AHS, is now part of the UVM Network’s senior management team. “As second-in command to Brumsted, Gobeille is assumed by many to be his successor.” That makes Schubart sound like an insider, but he obviously doesn’t get it. The actual selection of a new CEO for the network is most likely to come from outside Vermont. There are a handful of potential in-house candidates including Al Gobeille and Dr. Steve Leffler. If there is an internal successor to Brumsted, it is much more likely to be Leffler, who is President of UVMMC, or whoever fills the vacant post of head of the Medical Group, the physicians who practice mostly in Burlington.

After this meandering mess, Schubart goes off the rails by suggesting that the travails of the UVM Network are leading to something much darker.

And when does self-interest metastasize into corruption?

In watching and participating in health care reform in Vermont over the last 38 years, that is the single most irresponsible thing I have ever heard said.

To sum up, the threats to a reform future, one that saves Vermonters billions of dollars going forward and drives badly-needed improvements in quality across the entire state, are players like Doug Hoffer, the state auditor; several Chittenden County Progressives, like former Sen. Tim Ashe, and current Sens. Chris Pearson and Michael Sirotkin; a big chunk of the small hospitals who are desperate to keep delivering care that is too complex and expensive for them to manage; VTDigger, the only state-wide news organ, whose performance on health care is a journalistic disgrace; a random collection of cranks, yahoos and know-nothings; and, now Bill Schubart.

I will leave my tiny corps of brilliant readers with this conclusion:

You can believe what you hear from this malignant tribe. You can also believe in the Easter Bunny.

N.B. In the current debased public policy space it isn’t enough to just lay out a skein of facts—you basically have to prove everything. And even then, you can expect that more than 40 percent of the public will continue to reject it out of hand. The following elements would be footnotes in a longer treatment:

On the legal status of OneCare Vermont:

OneCare Vermont is a limited liability for profit corporation organized under Vermont state law, Title VSA 11 Section 4002. It is a for-profit company in Vermont. It doesn’t get profits, but it can’t get non-profit status under Vermont law without constraining the percentage of active players on its governing body to 50 percent of the members. Under pressure from Mike Smith, the Secretary the Agency of Human Services, OneCare petitioned the federal government to shift its tax status to non-profit. In response, the Internal Revenue Service agreed to “recognize” its non-profit under Title 26 United States Code, Section 501(c)(3), but its Vermont status remains for profit. It was a huge issue when Smith pushed for it, and it lingers in the drumbeat of criticism about OCV generally; but in fact, the whole exchange made no change in the way the system actually works.

When it started out, OneCare crafted an Operating Agreement to govern the way the members dealt with each other; the specifics of that agreement are not set forth in state law, but the contract among the members is enforceable by a Vermont Superior Court. Following are the relevant portions of the OneCare Operating Agreement:

Paragraph 4.2: Actions Requiring Supermajority Approval of the Board. Notwithstanding any other provision of this Agreement to the contrary, without the approval of a supermajority of the Board, which for purposes of this Agreement means the vote of two-thirds (2/3) or 66.67% or more of the Managers eligible to vote, including the vote of at least one of the Appointed Managers appointed by UVM Health Network (such approval, a “Supermajority Approval”), the Company shall not take any of the following actions:

(c) Execute any instrument, ACO Program Agreement, or take any action to bind the Company to any fixed or contingent obligation in excess of $100,000;

(e) Guarantee the payment of money or the performance of any contract by another person or entity where the obligation to pay exceeds $100,000;

and,

Paragraph 6.1: (m) Adopt the annual operating or capital budget of the Company (notwithstanding any other provisions, expenditures in approved budgets do not require additional approval);

(n) Adapt or materially modify the Clinical Model, or any plan for the allocation of programmatic shared savings or shared risk in the ACO;

(o) Adopt any strategic plan for the Company;

(p) Execute any contract with a monetary value in excess of $100,000;

(r) Any Other Material Action. For purposes of this Agreement, the term Material Action shall mean any action that is determined by a Member in its discretion to involve a material change to the operations of the company or has a financial impact on a Member greater than $100,000.

If you read and think about that boilerplate, you can see that jimmying the money by UVM is about as impossible as one can get. Look particularly at (r), which says in effect that whatever else happens, any member can call for a supermajority vote, irrespective of the merits of the case. And if it happens that a single hospital was to lose such a vote, it can simply opt out of that contract, and revert to full fee-for-service reimbursement.