by Hamilton E. Davis

The assault on our species by the COVID-19 virus has inspired me to wonder about how my tiny corps of brilliant readers is coping with it, now that its full impact looms over our Green Mountain fastness. I don’t remember how or when I came up with the tiny corps formulation; it seemed at the time like a harmless, tongue-in-cheek acknowledgement that my audience is small. The more I have used it, however, the more it has struck me that my tiny corps isn’t really tongue-in-cheek anymore—it’s still tiny but I’ve come to believe the “brilliant” part. The reaction I get from my readers tells me that they really appreciate efforts at serious journalism. And I suspect that that hunger is the stronger because serious journalism is hard to get, especially in Vermont. Hence, a new formulation—The Virus Papers.

The fact that the flow of information to the public amounted to pretty thin gruel struck me a week or two ago, and it wasn’t limited to Vermont. I kept reading, in places like the New York Times and Wall Street Journal as well as the usual web suspects, that there “weren’t enough test kits” to determine who had the virus and who didn’t. For several days, it seemed like it was “test kits, test kits, test kits” all the time, set in a context that included huge failures by the Trump administration, turf wars between the Centers for Disease Control and the Federal Trade Commission and a surfeit of political back-and-forth between Democrats and Republicans. It wasn’t difficult to follow the national trends, or the political thrust and parry in Washington, but I was particularly anxious to figure out just where we were in Vermont.

Where are we on March 24?

As far as Vermont was concerned, I began looking for what seemed to me would be the basic information you would need to figure out what was going on. How many staffed hospital beds do we have? How many ICUs, because the virus attacks the lungs? How many ventilators, for the same reason? And when you mush all of that together, how many beds do we have for very sick people?

Beyond that, what would the experience of other countries, as well as other states in the United States, tell us about what we could expect in Vermont? And still further beyond, what could we do in Vermont to deflect the beast?

Until about the middle of last week, it seemed very hard to get what I think is basic information about our armamentarium, number of beds, etc. Governor Phil Scott and other officials were urging people to keep a distance between individuals, avoid crowds, wash their hands. Schools and colleges were sending students home, restaurants and other gathering places were shutting down. But the virus was continuing to build and I still couldn’t get the basics.

At that point, however, things started to move. Scott held a news conference that I called into and in the wake of the governor’s remarks, Mike Smith, the Secretary of Human Services began answering pointed questions from the press. Like, how many ventilators do we have? Smith just answered it, around 210, which answered one of my questions—would state officials avoid specifics in an effort to avoid scaring the public. Nope, the number was 210, with no sugar coating, even though that number was far below what any surge number of cases would require. The Seven Days weekly magazine carried some of the specifics, albeit without much context; but on Sunday, Mar. 22, VTDigger cobbled together the best picture yet available on what we have available medically to deal with the expected surge of patients over the next few weeks.

It looks like this:

961 total hospital beds, 99 intensive care unit (ICU) beds, 210 ventilators

That is the baseline of the capacity that exists in the state. A key question is what percentage of those beds would be available for virus patients. Hospitals can postpone stuff like elective surgery, but they will have to continue to care for patients coming in with routine medical problems—heart attacks, strokes, cancer care, accident victims, and so forth. In a recent press conference, Mike Smith, Secretary of Human Services, said that number was 500 beds. Hospital managers have been planning to open up new spaces for virus beds, but it isn’t clear how much that will help: the ceiling is more the equipment available, like ventilators, and even more importantly the people to deliver the care.

When you start to put together all the available information it quickly becomes clear that Vermont can’t handle a surge of cases that is not just likely, but virtually certain. Jeff Tieman, the president and CEO of the Vermont hospital association, put it succinctly:

It is literally not possible to be ready for something at the level we’re facing right now.

So, what do we know about the virus at this point, and can we foresee when the growth in the number of infected patients will exceed the capacity of our health care system? In looking at this question, I am working with Easton White, Ph.D., a research associate at the University of Vermont. White is a biological modeler whose research specialty is quantifying how populations change over time, including examining the movement of disease through animal groups. “Working with” means I ask him questions and he figures out the answers.

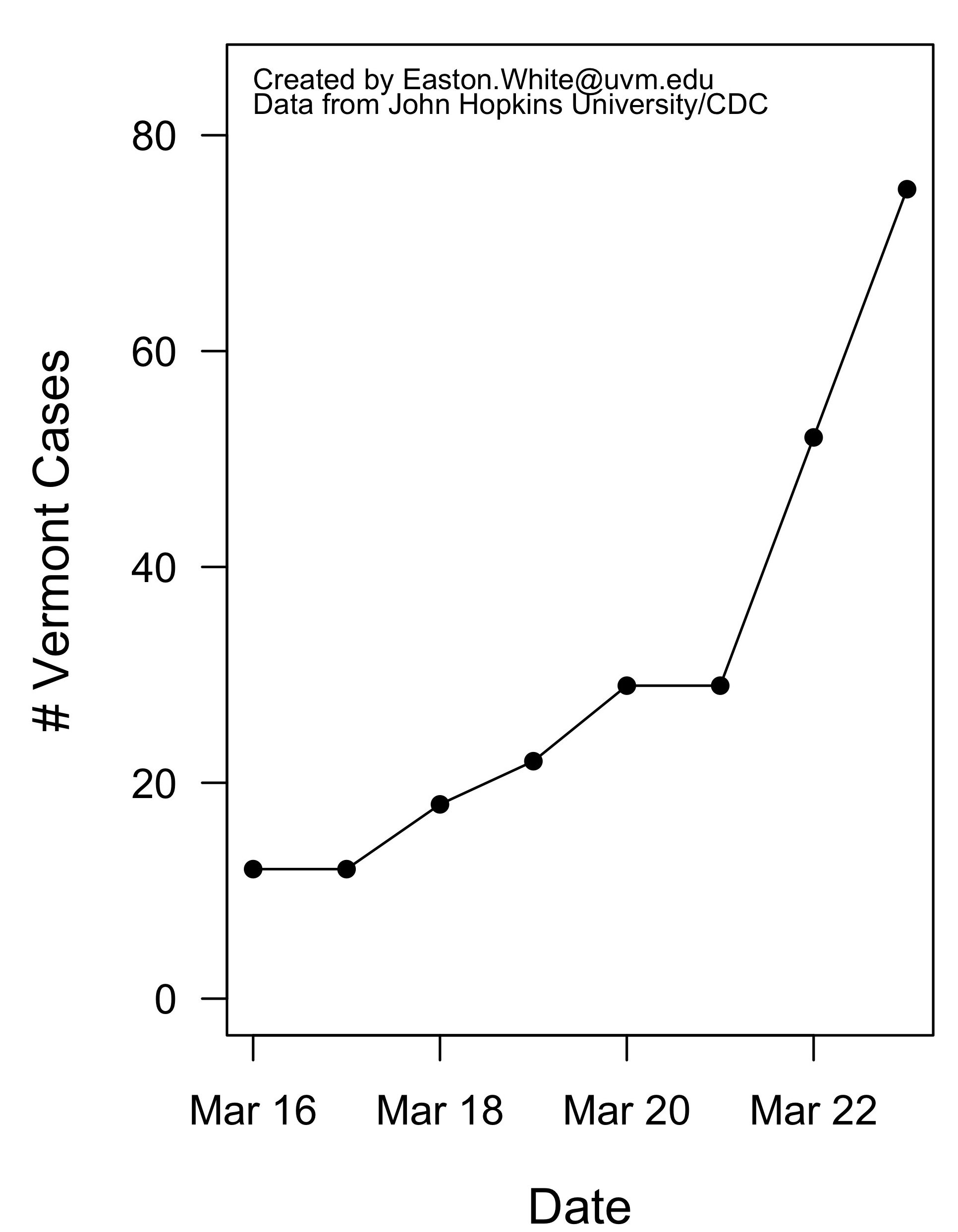

As of the end of the day Monday, March 23, the number of infected Vermonters stood at 75. The first Vermont case was reported in early March. The raw data looks like this:

Raw Data

Date Cases

2020-03-16 12

2020-03-17 12

2020-03-18 18

2020-03-19 22

2020-03-20 29

2020-03-21 29

2020-03-22 52

2020-03-23 75

When you graph that, it falls into the classic mathematical pattern of exponential increase. Exponential increase means simply that the rate of growth is proportional to the population size. If you start with 2-squared, for example, you get 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128…an exponential track starts out looking not-too-bad and then goes up really fast after you get out a ways. Here is a graph showing the track of the Vermont data from the table above. It’s exponential, like most if not all of the United States, and the worst-hit countries in other parts of the world.

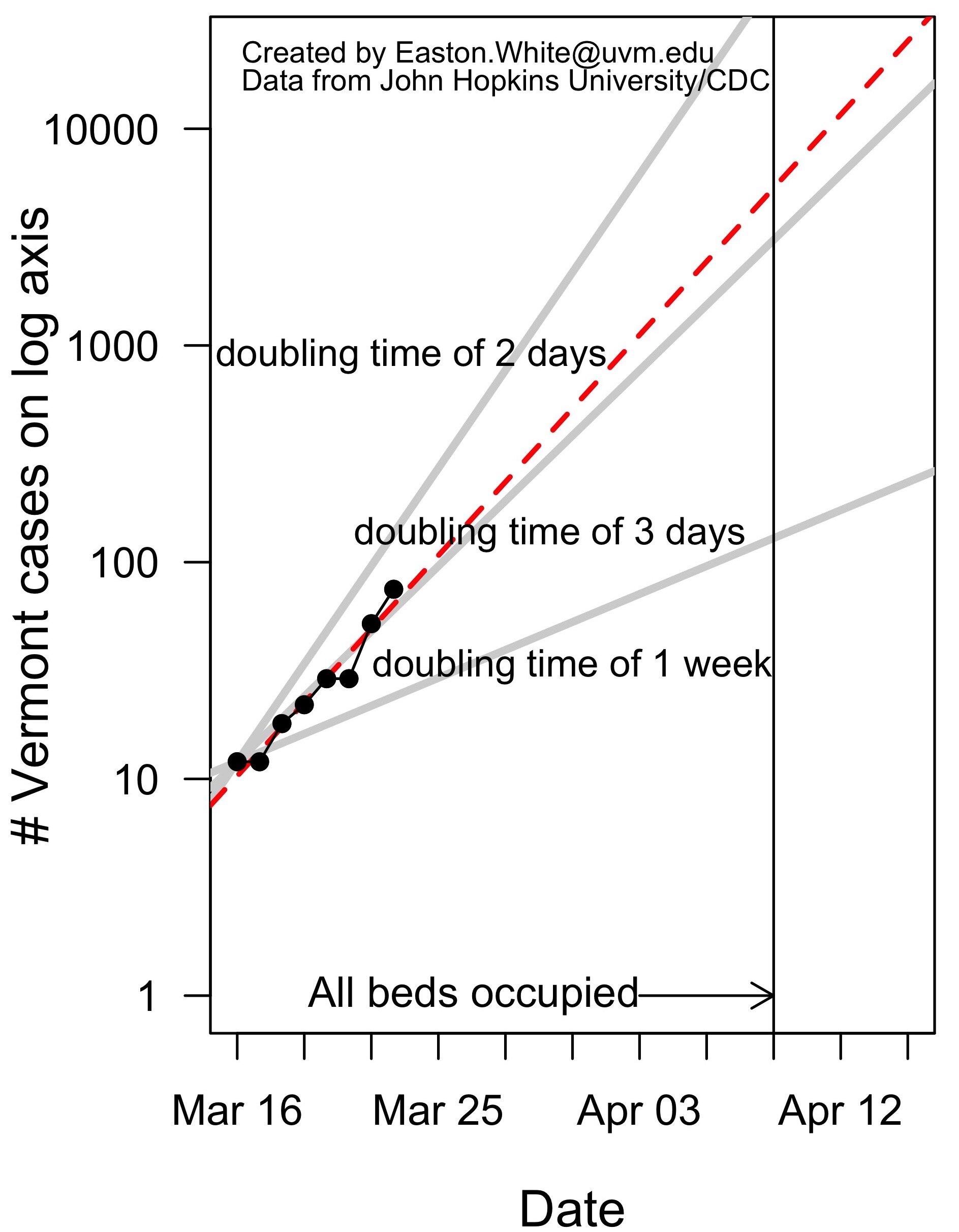

A critical question in trying to suss out the impact of the virus trend on Vermont is to determine the doubling interval, the time it takes for the number of cases to double. The longer you can stretch out the doubling interval the better chance the medical system has to deal with the patient load without crashing. The way you get at the doubling interval is to express the raw data in logarithmic form, which converts the track of the raw data to a straight line, whose slope can be measured, and the slope is used to find the doubling interval. Hence:

White’s calculations show that the Vermont doubling period is every three days. If we stay on our current track the number of virus victims in the state will blow by Vermont’s hospital capacity sometime in the second week in April. Can that crux point be stretched out, or even suppressed enough that the health care capacity never gets breached?

The Digger story wanders around quite a bit but read all the quotes: what all those professionals are saying amounts to—we hope so, but we have no idea how. And the few I have talked to believe the chances are slim to none. We all have to be prepared psychologically for the doubters to be right.

N.B. I’ll post some further editions of the Virus Papers over the next few weeks. Coming tomorrow—why we can’t match Korea.