by Hamilton E. Davis

Things to cogitate on in Green Mountain Lockdown: none of us has ever experienced anything like this before, and it’s interesting to wonder what we will learn from it, as individuals and as a society. Some lessons are obvious already—it’s sub-optimal for example to have a venal and incompetent national government; and it’s likely that we won’t soon forget that it was unwise for federal officials (not the Trumpies) to forget to restock the national supply of surgical masks. Yet, the ambition and reach of the current virus is taking us to places we’ve never been before.

One of the most important things we all have to figure out is the extent to which we can depend on a passive defense against a dangerous virus. The two countries that hammered the beast into submission in a relatively short time were China and South Korea. They did so using two basic tools—virtually unlimited testing, and aggressive tracking. The formula: test everybody you possibly can. When you find an infected person, isolate him or her, and then interview that person to find out others with whom the infectee has been in contact. Then test those people and carry out the drill all over again. What it amounts to is chasing down every edition of the virus and starving it of new hosts. That is an active defense.

It will be argued, of course, that China cannot be a model for the United States because of its brutal social and political control, and its indifference to suffering on the part of its people. South Korea, however, is a democratic society, and the active defense there seems to have worked. At a minimum, the South Koreans flattened the virus curve far better than any western country, including Italy, Germany, the UK and the United States. Could we emulate the South Koreans?

There is certainly no intrinsic barrier to getting enough testing material. Our failure to accomplish that was simple incompetence, which can be corrected. We will pass at least two generations before we make an error that stupid again. A much harder question is actively tracking each individual virus through the population. We would have to do so without sacrificing individual liberties; and even assuming we could devise an acceptable algorithm in that regard, it is hard to imagine the human tracking machinery necessary to follow the winding path each individual virus takes through a population of more than 300 million people.

Still, it shouldn’t be impossible. And for those who would bemoan its cost and complexity, I would suggest: Take a look around. The virus has blown our economy to smithereens. We’re all sitting around in lock-down, our businesses, our educations, our lives on hold. Those of us not on lock-down are tearing around trying to keep us alive and risking their health in the process. The total cost is already in the trillions of dollars, and we haven’t hit bottom yet, the narcissistic fantasies of Donald Trump to the contrary notwithstanding.

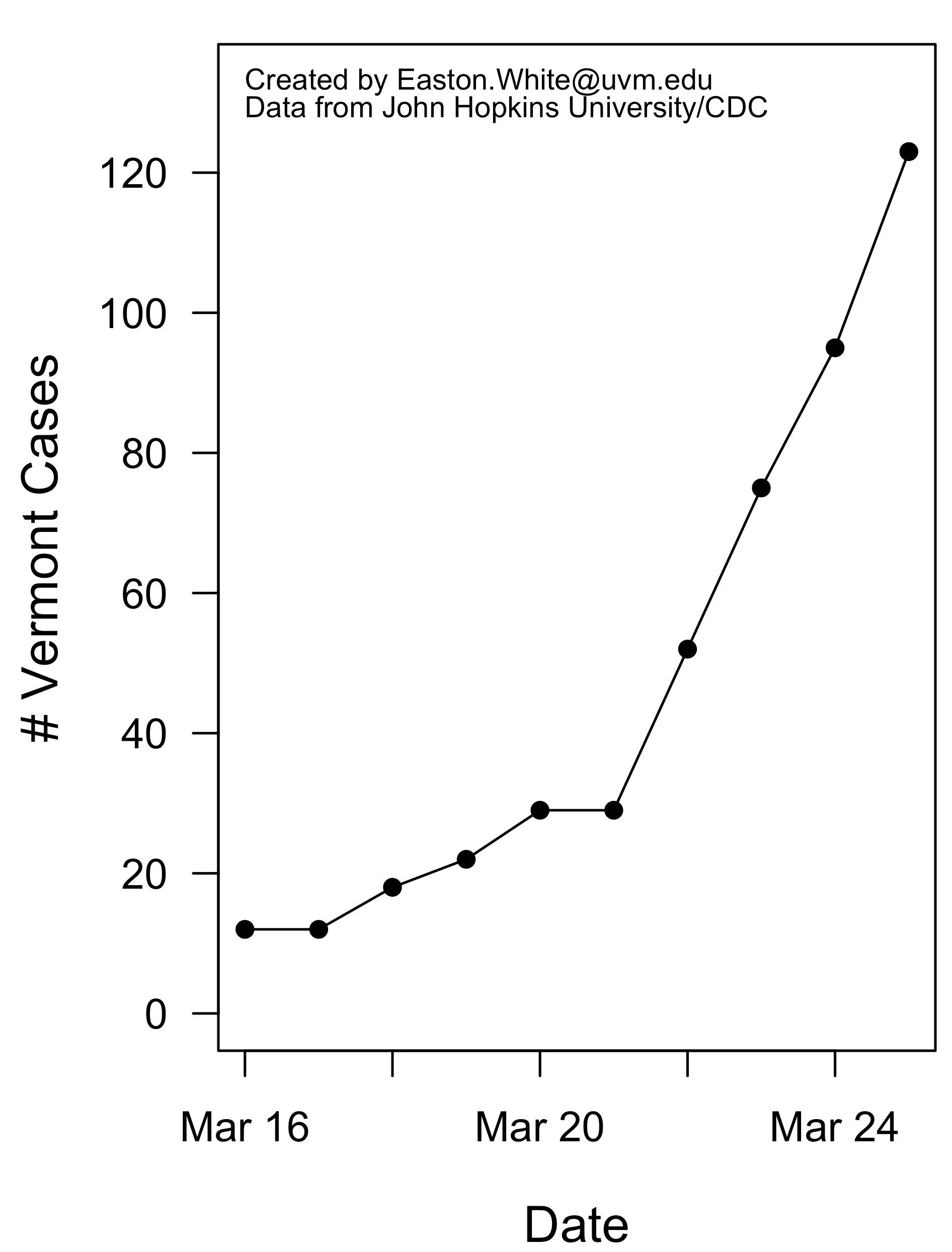

The other side of that conundrum is the final accounting we will have to make of the efficacy of our passive defense. We have implemented what feels like draconian steps to limit individual contact and hence the speed of virus movement through the population. It is a serious question whether those steps were taken soon enough, but they are clearly here now—there’s no evidence yet, however, that they have shifted the doubling curve. In my first Virus paper, I showed the raw data for the increase in infected patients, starting with the first couple of cases and topping out at 75. When plotted on a graph, the trajectory was exponential, which means that the numbers were doubling over some period—a day, two days, three days, a week…when those data were graphed by the logarithms of the raw data, they fell into a straight line on a doubling rate of three days. Easton White, a research associate at the University of Vermont has updated the graph of the raw data, and logarithmic treatment that shows the doubling interval.

The number of Vermont cases as of Thursday morning was 123, which is still roughly on the three-day trend, so there is not as yet any indication that our passive defenses have bent the curve downward.

A significant problem with these data is that there is no way to tell whether the daily progression of the numbers is being driven by the testing pattern, or by the increase in the absolute number of cases—or both. In Mathland, the problem is there is no “counterfactual,” which means that we have no way to tell what the rate of increase would be if we weren’t reacting to the virus at all. Italy has sent a strong message that we would be much worse off, but “worse” is not a number.

In the last 24 hours, Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York has said he thinks that the rate of increase of new cases in his state, principally in New York City, is easing a little, which could imply that the passive defenses are beginning to bite. But it is too early to draw any firm conclusions on that yet. In Vermont, we’re still exponential. The first optimistic sign here will be a marked increase in the doubling period, to, say, a week or more. But even there, it will take some time to wash out the counterfactual problem.

When the waters finally recede, we will be able to tote up the cost and efficacy of the passive defense. We can consider then whether we should build an active defense capability, which will be a fascinating policy discussion, in Vermont and the rest of the country. Think about it, for most of us there’s not much else to do.