by Hamilton E. Davis

In my most recent post, I suggested a solution to the most difficult challenge standing in the way of full maturation of Vermont’s health care reform project. The challenge is to right-size the state’s community hospital system, which today makes no medical or financial sense.

The essence of the Manifesto called for maintaining and extending full hospital operations in Burlington, Rutland, Berlin, Bennington and implicitly, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in nearby New Hampshire, which delivers tertiary care to the eastern half of the state. The remaining 10 smaller hospitals should be stepped down to clinics of various capacities, depending on local circumstances. The basic task there is to provide strong primary care and emergency services, and possibly maternity care.

What needs to be scrubbed from the community hospitals is care, much of it surgery, that has too little volume to ensure that the doctors and support teams stay clinically sharp as well as too little volume to enable a hospital to achieve a unit price that makes sense. If your hospital is performing 27 hip replacements a year, then the cost per case of maintaining the resources to do hip replacements is a huge waste of money. A Vermont example of that was the maternity unit at Springfield Hospital that was delivering 125 babies a year, a little more than two babies per week. That mismatch was a major contributor to the hospital losing $150,000 a week on its way to bankruptcy court in Rutland. A New York example was the heart bypass operation at the hospital in Plattsburgh, which was doing 110 bypasses a year and helping the hospital to lose $5 million a year — not to mention that the quality was just plain bad. I covered this in a previous post on reform efforts in New York’s North Country.

Despite the obvious need, executing the right-sizing effort would be hugely difficult under the best of circumstances. It will be incomparably more difficult in the face of the full-throated opposition from all the state’s hospitals, including the UVM health network, whose leadership knows, better than anybody else, how critical it is to rationalize the system going forward. After all, the network has already carried out just such an exercise in northeastern New York State: the result put a collapsing four-hospital system there on a solid footing for the first time in four decades.

The importance of getting this right, and getting it right as rapidly as possible, cannot be overstated. Small rural hospitals are crashing all over the country because they are too small to keep up with the complexity and soaring costs of 21st century medicine. The remedy nationally is a wave of outright closings or consolidation into much bigger organizations that are converting increased size into outsized market power. Check out the stock performance of United Health Group: 2019 revenue $242.2 billion; stock price more than doubled since 2016.

The only place in the country where that dynamic is not present is the Vermont hospital system, but the Vermont reform project, and the whole system itself, is in crisis. That squawking you can hear in the distance is every Vermont health policy chicken coming home to roost right now. The loudest squawking is coming from the Vermont hospitals themselves. It sounds clearly in letters that the hospital association chief Jeff Tieman, the CEO of the Vermont Association of Hospitals and Health systems, wrote to the Green Mountain Care Board on March 11 and August 4, and in Tieman’s testimony to the Board on July 15.

Tieman’s basic case is that all the hospitals are needed to deliver care in their current configuration to their communities; that they have no time or ability or need to examine, explain or justify what they do; that the Green Mountain Care Board is overreaching its authority by even asking those questions; and that the Board should just give them the money they say they need. Of course, the hospitals say they are all-in on reform, but that even looking at what is actually going on is a “conversation for another day.” Have I overstated the situation? Let’s look at the Tieman case.

The Hospital Case

Let’s start by unpacking Tieman’s March 11 letter to Kevin Mullin, chairman of the Green Mountain Care Board. Tieman is the spokesman for the hospitals, but his letters, including the March 11 version and a similar, slightly toned-down missive on Aug. 4, were signed by all the hospital CEOs along with some other major players.

Tieman’s first point is that the hospitals “are leading the way in reform” but that the demands of the Green Mountain Care Board are imposing an increasing administrative burden “without a clear benefit.” That is particularly difficult now, he asserted, while the hospitals are fully engaged in trying to manage the Covid-19 crisis. “At all times we must be fully prepared and adequately resourced to meet community need—even a brand new and rapidly evolving need like Covid-19,” he wrote.

These points amount basically to lobbying against what hospitals just don’t want to do. In the first place, the “hospitals” are not leading the way to reform. The UVM system is leading the way, but the others are just trying to keep their noses above water. The hospital association posture is driven entirely by the small hospitals, and has been since reform was first bruited eight years ago. Bea Grauce, Tieman’s predecessor, horrified by the idea of a 3.5 percent cap on annual hospital inflation, warned that the hospitals might not be able “to accomplish their mission” — the classic ‘Your Money or Your Life’ ploy. (The cap actually has worked well) The Tieman argument is squarely in the same vein.

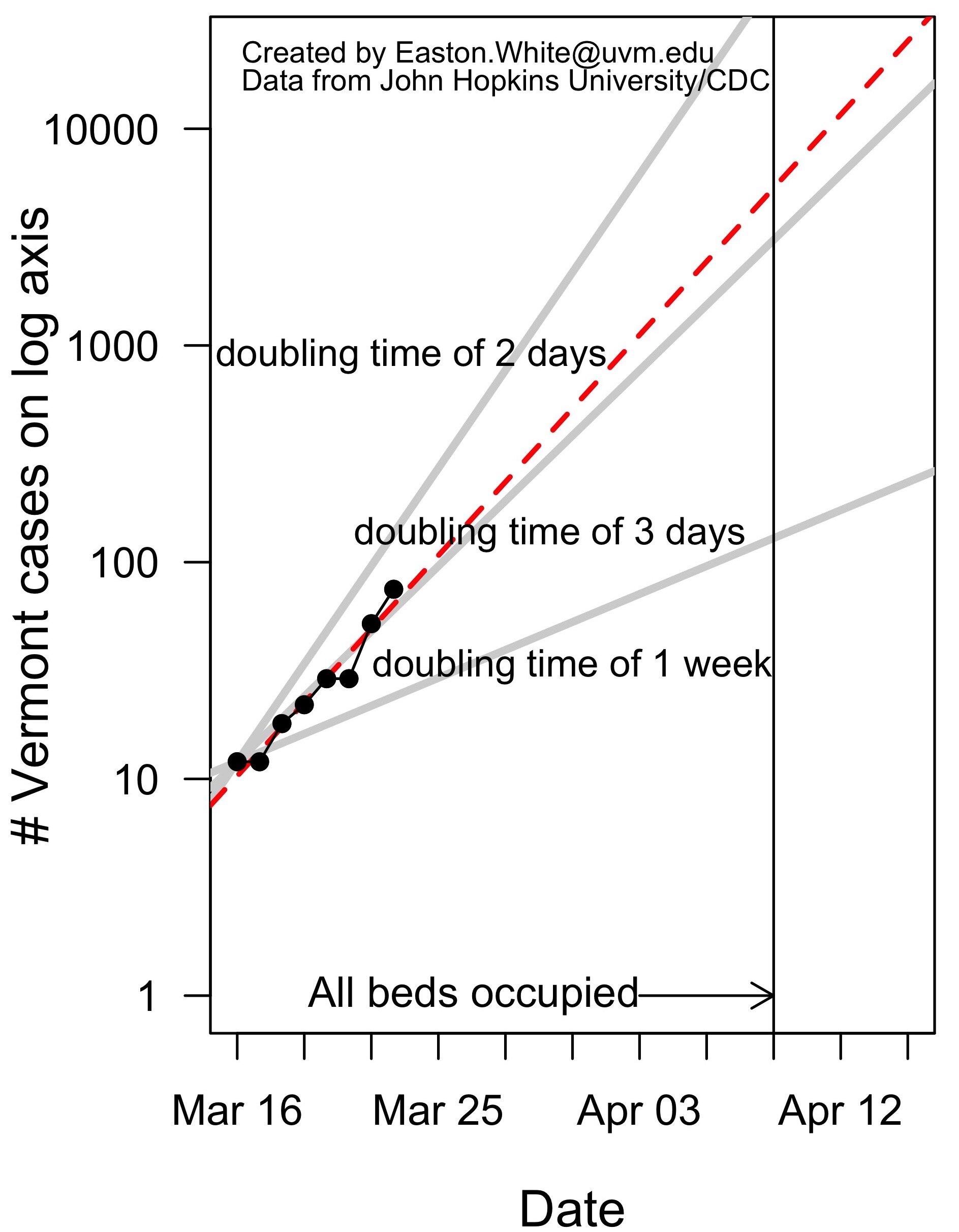

Secondly, the claim that the hospitals are the bulwark against Covid really doesn’t stand up to examination. All the hospitals suffered financially from the loss of revenue during the four months they were shut down, but a major piece of that damage is being made up by federal help, and the hospitals are now back to full operations. The fact is that Vermont hospitals had hardly any actual Covid traffic. The Tieman letter also asserts that, medically, the hospitals are still fully engaged by the virus. That is just inflated rhetoric: According to Dr. Mark Levine, the health commissioner, his office gets regular reports on hospitalized Covid cases, and the number varies from zero to two. That’s for 14 hospitals. Even the statewide number for people under observation in a hospital runs to the mid-teens or less; and almost none of those actually have the disease, Levine said. If a medical organization can’t handle that level routinely it shouldn’t be a hospital. And if a community hospital has a Covid case where the life of the patient is truly at risk, it should transfer the patient to a tertiary center, or at least a facility with a full ICU.

The hospital’s second major demand is that the Green Mountain Care Board move away from a common inflation target and judge hospitals based on their individual performance. Specifically, the Board should acknowledge factors that are beyond the hospitals’ control, including drug prices; salary and wage growth, “given Vermont’s limited and shrinking work force; expense growth owing to aging patients. Finally, the Board should “Base budget decisions on objective data and information.”

Making hospital decisions on a case-by-case basis is a perfectly reasonable proposition, which is probably why the Board does it now. Example: in the 2019 budget hearings, the Board the allowed UVM to charge private insurers two percent more than the year before, while allowing Copley Hospital to increase the same charges 9.8 percent. Different situation, different decision. Happens all the time. Also, pretty striking for the hospitals to describe the salaries they pay as beyond their control. Who else controls them? From 2000 to 2009, every Vermont hospital doubled its budget, and the bulk of that money went to huge salary increases for bigfoot doctors and administrators. And, finally, “Base budget decisions on objective data and information?” That is precisely what the Board is trying to do with its call for sustainability plans, and it is precisely that which the hospitals are terrified of; and it is why Jeff Tieman is desperately trying to fend off the idea. He knows, and every signer of his letters knows, that the current organization of the community hospital network makes no sense medically or financially.

Which is the reason for the main case made by the hospitals in the two Tieman letters and in his testimony to the Board on July 15. The hospitals’ main objection is to the Board’s demand for “sustainability plans” from at least six small hospitals, and possibly more. That issue has been on the table for a full year now, and the small hospitals are totally opposed because they know their current business models are, in fact, not sustainable. Tieman’s specific points in his two letters to the Board:

Too much information is being asked for.

The small hospitals do not have the ability to determine the cost efficiency of their various service lines.

The Green Mountain Care Board request “exceeds the reasonable statutory authority of the Board. GMCB has authority to approve hospital budgets. Any sustainability plan must fit within this context. Themes intended to be addressed by the budget process—e.g., efficient and economic hospital operation, adherence to peer group norms and provision of an integrated holistic system of care-- are lost in the proposed service line analysis.”

And the take home message on reform:

“If sustainability means ensuring each hospital can keep serving its patients and communities, then it is achieved as part of the GMCB’s already exhaustive annual budget review.

“If sustainability means planning and managing the next iterations of health reform and system transformation, that is an important but different conversation.”

There is some more in the hospital screed, but my tiny corps doesn’t need to look much further than the last paragraph. The “efficient and economic hospital operation, adherence to peer group norms and provision of an integrated holistic system of care” are exactly what the system needs, exactly what it doesn’t now have, exactly what the GMCB needs the relevant data to pursue, and exactly what the hospitals are fighting hard to avoid giving them.

Failure to engage with this issue now would be devastating to reform, and to the health of the Vermont system as it enters the third decade of the new millennium. There’s a big chunk of federal money now available to hospitals and it could be spent on putting them onto a sustainable track, or it could be used to just keep trying to fend off the inevitable. Moreover, when the Covid beast goes away, the “smalls” are going to find that neither the federal government, nor state government, nor private insurers will be able to pay the price for a palpably unaffordable system.

We won’t have to wait long to see how this policy conundrum gets resolved. The Green Mountain Care Board will hold its first 2021 hospital budget hearing today. The decisions on the well-north-of $2 billion dollar system have to be reached by late September.

Cross your fingers.